Technologie suisse de haut vol :

bienvenue dans l’étendue infinie de l’espace

Le fantastique voyage débute à l’université de Berne. Les étudiants sont assis dehors, tandis que professeurs et doctorants déambulent dans la douce brise d’octobre devant le bâtiment principal. Un grand soleil bien jaune brille sur la Suisse comme s’il n’y avait qu’une seule étoile là-haut.

À l’institut de physique, une porte en verre mène au département de la recherche spatiale et de la planétologie : bienvenue au Center for Space and Habitability.

Les murs du hall sont tapissés d’affiches représentant des fusées et des ovnis. Des satellites gravitent autour de lunes violettes, des petits hommes avec des antennes avancent sur des cratères. Les questions posées sur les affiches sont cependant extrêmement sérieuses. Existe-t-il une seconde Terre ? Existe-t-il d’autres planètes qui ne soient pas seulement constituées de gaz et de boue, mais qui possèdent une atmosphère ?

S’il y a bien un endroit où ces questions font l’objet d’une précision scientifique, c’est en Suisse ! Pourtant lorsque l’on évoque ce petit pays montagneux, beaucoup pensent d’abord au fromage, aux cloches de vache et aux montres de luxe.

Mais la Suisse ne se limite pas à cela ! L’Université de Berne a contribué aux alunissages dès les années 1960. Les voiles solaires des missions Apollo ont été développées ici, à l’Institut de physique. De nombreux instruments et appareils de mesure bernois sont en orbite ou sillonnent le système solaire à bord de sondes spatiales. En 1995, deux scientifiques suisses ont également localisé la première exoplanète. La découverte de 51 Pegasi b est considérée comme une étape importante en astronomie.

Des spectromètres bernois ont déjà été envoyés vers des comètes lointaines pour y analyser l’atmosphère. D’autres appareils de mesure des laboratoires suisses ont volé vers Jupiter et le Soleil. Il suffit de jeter un œil à la liste des missions spatiales auxquelles la Suisse participe pour n’avoir qu’une seule envie : décoller.

Il est question de voyages vers Mars et Vénus ou encore de l’analyse du plasma spatial. Des sondes seront envoyées jusqu’aux lunes glacées de Jupiter avec à leur bord des instruments de précision bernois. Ceux-ci sont là pour déterminer s’il existe des traces de vie dans les profondeurs océaniques des trois lunes Ganymède, Callisto et Europe.

Les questions posées sont existentielles. Comment l’univers a-t-il été créé ? Comment la vie est-elle apparue sur Terre ? Un voyage fascinant, sans doute le plus audacieux que les terriens n’aient jamais entrepris.

La mission « PlanetS » est en cours. Elle doit nous permettre de comprendre les composants des planètes et de déterminer si la vie y est possible. Pour ce faire, des sondes collectent des échantillons de roche et des données d’astéroïdes, comètes et météorites lointains. Ces objets venus de loin présentent-ils une biosignature ? Et si oui, laquelle ?

À l’institut des Sciences exactes, Nikita Boeren et Peter Keresztes Schmidt s’activent ce matin. Ces doctorants en physique et astrochimie consacrent leurs recherches principalement aux étoiles. Alors que certains connaissent le prix du beurre de supermarché, eux peuvent réciter par cœur les bases de l’astronomie. Ils perpétuent ainsi une longue tradition, Albert Einstein lui-même ayant donné des conférences à la faculté suisse.

Entre 1902 et 1909, Einstein passa ses « heureuses années bernoises » en Suisse. C’est ici qu’il développa la théorie de la relativité en 1905 et qu’il commença à enseigner en 1908. Il dispensa son premier cours portant le titre de « Théorie moléculaire de la chaleur » à sept heures du matin. Seuls trois étudiants étaient assis dans la salle ce matin-là et rapidement il n’en resta plus qu’un face au génie. Einstein n’était pas encore une star de la physique, plutôt un excentrique qui dessinait de drôles de cercles au tableau.

Aujourd’hui les astronomes empruntent l’ascenseur pour se rendre au premier étage. « Bienvenue dans notre bureau », dit Peter Keresztes Schmidt. Sur la table se trouvent des fraises, des pinces et des pincettes de précision. Derrière des rideaux, une salle blanche avec une machine argentée et une paillasse de sécurité microbiologique. C’est dans ce laboratoire spatial suisse que sont construits les instruments de mesure pour les futurs vols interplanétaires.

Des spectromètres de masse revêtus d’or doivent être envoyés vers la Lune lors d’une mission de la NASA. Une fois sur place, un faisceau laser pulvérisera la roche, après quoi les fragments ionisés seront séparés dans le spectromètre en fonction de leur masse atomique. L’objectif des chercheurs est de déterminer la composition de la roche. Peter Keresztes Schmidt explique : « Cette méthode nous permet d’identifier sur site les éléments qui se trouvent sur la Lune. Aluminium, fer, d’autres substances peut-être... Ces informations sont d’une importance capitale si nous voulons établir une présence sur la Lune. »

Une présence ?

« Oui, par exemple une station spatiale qui nous permettrait de poursuivre notre route vers mars. »

Après le déjeuner, Martin Rubin nous rejoint. Ce planétologue et chercheur spécialisé en comètes a participé à la mission Rosetta de l’ESA au cours de laquelle des spectromètres de masse et des capteurs de pression suisses se sont approchés de la comète 67P/Tchourioumov-Guérassimenko. Les capteurs de précision embarqués à bord devaient analyser les gaz et les particules de glace qui s’échappaient pour découvrir le mystère de la formation des planètes.

Rubin explique : « La comète a 4,5 milliards d’années, mais ses molécules d’hydrogène et d’hélium datent encore du Big Bang qui s’est produit il y a 13,8 milliards d’années. Les comètes sont les témoins de l’histoire de la formation de notre système solaire. »

Mais une question nous brûle les lèvres. Qu’y avait-il avant le Big Bang ? Martin Rubin porte des baskets et un sweat-shirt bleu. Il poursuit : « Nous l’ignorons. Et impossible de l’imaginer. Avant il n’y avait ni espace ni temps. Avant le Big Bang c’était l’opposé de l’infini. »

Dans son laboratoire, Martin Rubin fabrique également des instruments qui voyagent dans le vide cosmique à bord de sondes et de satellites. Il y a des appareils et des cylindres partout, une montagne d’équipements qui laisserait même Géo Trouvetou bouche bée. Martin Rubin pointe du doigt l’un de ces appareils : « Ce spectromètre de masse à temps de vol devrait s’envoler vers une comète en 2029 afin de répondre à d’autres questions. »

Mais la Suisse s’ouvre à des horizons encore plus lointains : aux confins de l’espace et du temps. Pour apercevoir de telles perspectives intergalactiques, direction Zermatt. Cette ville alpine est un véritable havre de paix pour les visiteurs. Au village, crêperies, bars, boutiques et restaurants chics abondent. Tout là-haut, la star de la région règne en maître : le Cervin, une pyramide enneigée s’élevant verticalement vers le ciel.

Le deuxième plus haut chemin de fer à crémaillère à ciel ouvert d’Europe part de la station inférieure et effectue son ascension en direction de Gornergrat. La limite forestière approche, les névés défilent, puis il s’arrête : nous avons atteint 3.100 mètres d’altitude.

Tout autour se dressent des sommets de quatre mille mètres. Mais ce n’est pas tout : c’est aussi là que se trouve l’hôtel le plus haut de Suisse.

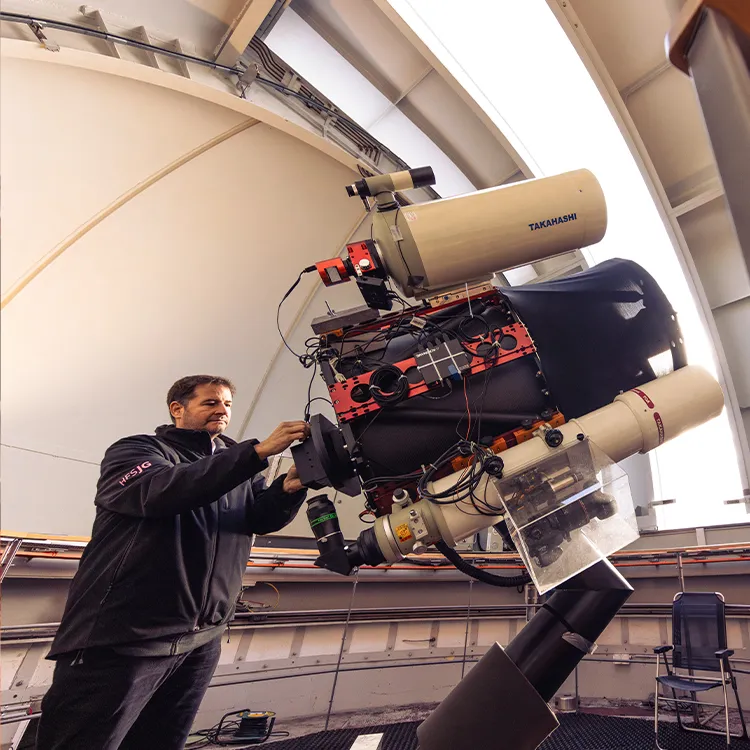

Le Kulmhotel Gornergart ressemble à un château fort flottant au-dessus des nuages. À l’intérieur, 22 chambres à la douce odeur de bois de pin, des salles de bains modernes et du linge de lit d’un blanc immaculé. Au rez-de-chaussée deux restaurants où sont exposées des œuvres d’art moderne et proposant des menus raffinés. Mais cet hôtel est bien plus qu’un simple hôtel, il abrite également le Stellarium Bornergrat, un observatoire d’où l’on peut observer les confins de l’univers.

Le directeur de l’observatoire est Timm Riesen, docteur en astrophysique et expert en spectrométrie de masse, galaxies et nébuleuses cosmiques. Il a passé six ans à Hawaï pour le compte de la NASA et était présent au lancement de la fusée Ariane 5 en Guyane française.

Il monte au sommet de la tour nord de l’hôtel. Ici, sous une grande coupole, se trouve « l’œil », le télescope. Timm Riesen ajoute : « La caméra Deep Sky nous permet d’observer l’univers jusqu’à 100 millions d’années-lumière de profondeur, prendre des photos d’amas de galaxies, d’étoiles binaires et de nébuleuses spirales lointaines. »

Timm Riesen pivote le télescope et les portes s’ouvrent. Derrière, on aperçoit un ciel nocturne glacial et des étoiles qui brillent. Certains phénomènes sont clairement visibles à travers l’oculaire de l’appareil. Les vrais mystères cependant sont révélés sur les écrans de l’ordinateur.

Il montre la nébuleuse d’Andromède. « Notre voisine dans l’espace », dit-il. « Une galaxie spirale située à 2,5 millions d’années-lumière. » Puis de nombreuses autres formations stellaires apparaissent sous la forme de motifs et constellations insolites. La nébuleuse de l’Aigle, la nébuleuse de l’Haltère, la galaxie du Tourbillon, l’amas de la Vierge. Timm Riesen ajoute : « Bien que tous se situent à 54 millions d’années-lumière, nous en faisons partie. »

Il fait un froid glacial sous la coupole du télescope. Au-dessus, la Voie lactée brille de mille feux. Timm Riesen poursuit son exposé. Selon les dernières découvertes, les chercheurs estiment qu’il y a quelque 200 milliards de galaxies rien que dans l’univers visible. Un chiffre qui dépasse l’imagination. Mais il y a encore mieux.

À la question de savoir s’il existe d’autres formes de vie, Timm Riesen répond : « Nous avons déjà découvert 5.000 exoplanètes. Selon des calculs récents, il doit existent entre 200 et 400 milliards d’étoiles comme le Soleil, autour desquelles gravitent autant de planètes. Les perspectives sont donc bonnes. »

De quelles perspectives parlez-vous ?

Timm Riesen précise : « De la probabilité qu’il existe d’autres formes de vie, qu’elles soient unicellulaires ou avec un peu de chance multicellulaires comme chez nous sur Terre. »

Auteur

Photographe

Aluminium Collection

Alliée de voyage

Parcourez le monde avec nous