An elevating experience:

See the Alps from a hot-air balloon

The transport vehicle: a gigantic balloon filled with nothing but hot air and driven only by the wind. It’s the oldest means of air transport in human history.

The guests have a general idea of what lies ahead. After all, they received a short briefing and the internet is full of photos and reports. But nobody knows exactly what it will feel like to be high in the sky in a hot-air balloon. To stand in a rattan basket, breathing oxygen, icy air at your feet and thousands of metres between you and the abyss.

The transport vehicle: a gigantic balloon filled with nothing but hot air and driven only by the wind. It’s the oldest means of air transport in human history.

The guests have a general idea of what lies ahead. After all, they received a short briefing and the internet is full of photos and reports. But nobody knows exactly what it will feel like to be high in the sky in a hot-air balloon. To stand in a rattan basket, breathing oxygen, icy air at your feet and thousands of metres between you and the abyss.

At the airfield, the gondolas are unloaded and a propane-fuelled burner sends hot air into the colourful envelopes. Very soon, they stand upright over the apron like gigantic airbags. Striding past the heavy bags, fans and lengths of line, Peter Flaggl prepares for take-off. The experienced pilot has 7,000 balloon flights under his belt. Dressed in leather boots and a blue anorak, he says: ‘Our balloon holds 9,200 cubic metres of air. That’s equivalent to 9.2 million litres of beer.’

Flaggl is the son of an experienced balloonist and a veteran of the air. He was only five when he first climbed into a rattan basket and sailed silently aloft. Flaggl thoroughly enjoys this type of air travel, particularly across the Alps.

Nobody knows exactly how long the journey will take. Once the balloons leave the ground, they can no longer be steered, but drift with the currents and become one with the wind. All you can adjust are the rates of climb and descent when the craft is in the air, floating off into the blue. The wind plays a crucial role. At over 5,000 metres, the balloon glides through the air completely disconnected from the ground. To float in humanity’s oldest aircraft is like drifting on an atmospheric whim.

At the airfield, the gondolas are unloaded and a propane-fuelled burner sends hot air into the colourful envelopes. Very soon, they stand upright over the apron like gigantic airbags. Striding past the heavy bags, fans and lengths of line, Peter Flaggl prepares for take-off. The experienced pilot has 7,000 balloon flights under his belt. Dressed in leather boots and a blue anorak, he says: ‘Our balloon holds 9,200 cubic metres of air. That’s equivalent to 9.2 million litres of beer.’

Flaggl is the son of an experienced balloonist and a veteran of the air. He was only five when he first climbed into a rattan basket and sailed silently aloft. Flaggl thoroughly enjoys this type of air travel, particularly across the Alps.

Nobody knows exactly how long the journey will take. Once the balloons leave the ground, they can no longer be steered, but drift with the currents and become one with the wind. All you can adjust are the rates of climb and descent when the craft is in the air, floating off into the blue. The wind plays a crucial role. At over 5,000 metres, the balloon glides through the air completely disconnected from the ground. To float in humanity’s oldest aircraft is like drifting on an atmospheric whim.

The principle couldn’t be simpler. Hot air has more kinetic energy and thus a lower density than cold air. It’s lighter, so it wants to rise. If this force is greater than the weight of the vehicle plus its occupants, a miracle occurs: the balloon leaves the ground.

At half past nine the passengers climb into the gondola. There are eight of us standing in small compartments open to the air. Above our heads, a giant dome filled with air. On the left in the gondola, Flaggl moves a lever to operate the burner. A column of hot air hisses skyward, heating the interior of the envelope to between 80 and 120 degrees.

On the apron, someone from the ground team untethers the last line. The gondola begins to move, pushing a bit of snow in its path. Leaving the earth behind, we begin silently floating upward. The airfield falls away below us. The village of Zell am See grows smaller, the houses, the church, the streets – all lose scale.

The principle couldn’t be simpler. Hot air has more kinetic energy and thus a lower density than cold air. It’s lighter, so it wants to rise. If this force is greater than the weight of the vehicle plus its occupants, a miracle occurs: the balloon leaves the ground.

At half past nine the passengers climb into the gondola. There are eight of us standing in small compartments open to the air. Above our heads, a giant dome filled with air. On the left in the gondola, Flaggl moves a lever to operate the burner. A column of hot air hisses skyward, heating the interior of the envelope to between 80 and 120 degrees.

On the apron, someone from the ground team untethers the last line. The gondola begins to move, pushing a bit of snow in its path. Leaving the earth behind, we begin silently floating upward. The airfield falls away below us. The village of Zell am See grows smaller, the houses, the church, the streets – all lose scale.

The principle couldn’t be simpler. Hot air has more kinetic energy and thus a lower density than cold air. It’s lighter, so it wants to rise. If this force is greater than the weight of the vehicle plus its occupants, a miracle occurs: the balloon leaves the ground.

At half past nine the passengers climb into the gondola. There are eight of us standing in small compartments open to the air. Above our heads, a giant dome filled with air. On the left in the gondola, Flaggl moves a lever to operate the burner. A column of hot air hisses skyward, heating the interior of the envelope to between 80 and 120 degrees.

On the apron, someone from the ground team untethers the last line. The gondola begins to move, pushing a bit of snow in its path. Leaving the earth behind, we begin silently floating upward. The airfield falls away below us. The village of Zell am See grows smaller, the houses, the church, the streets – all lose scale.

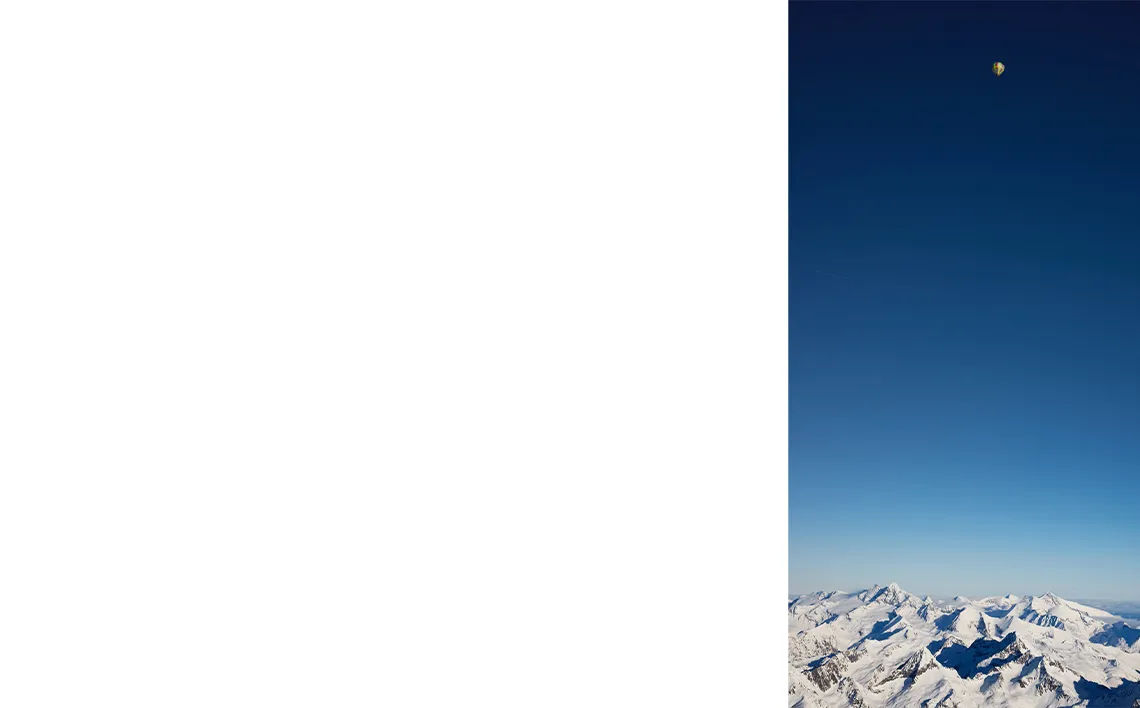

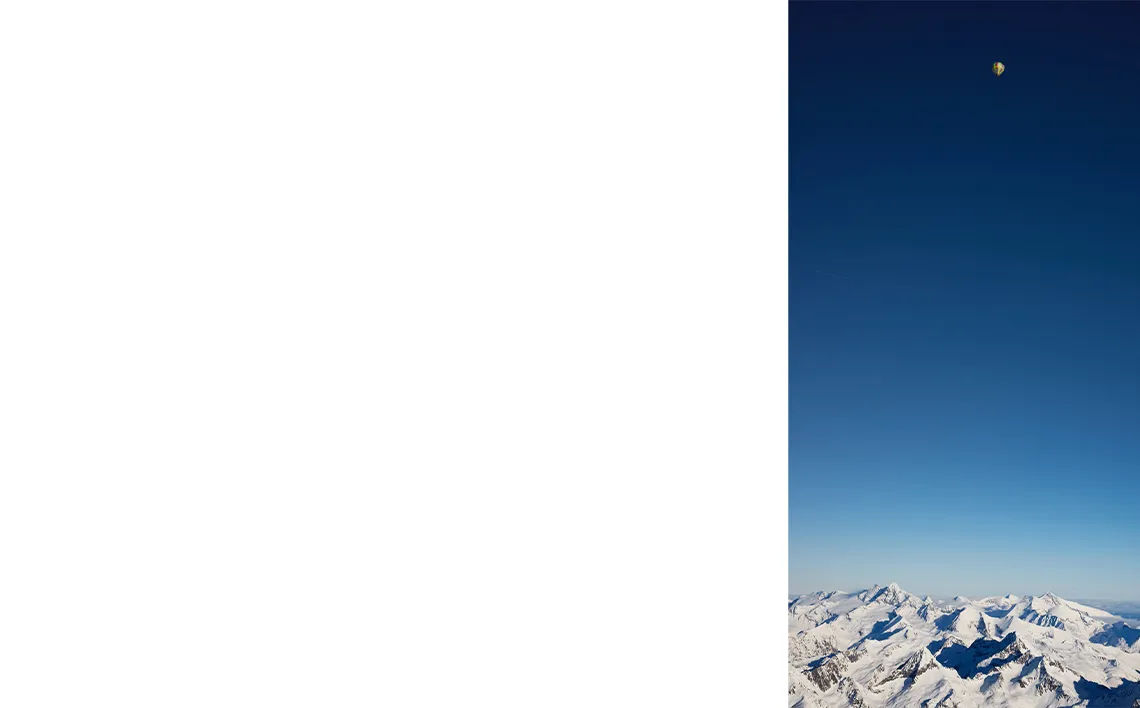

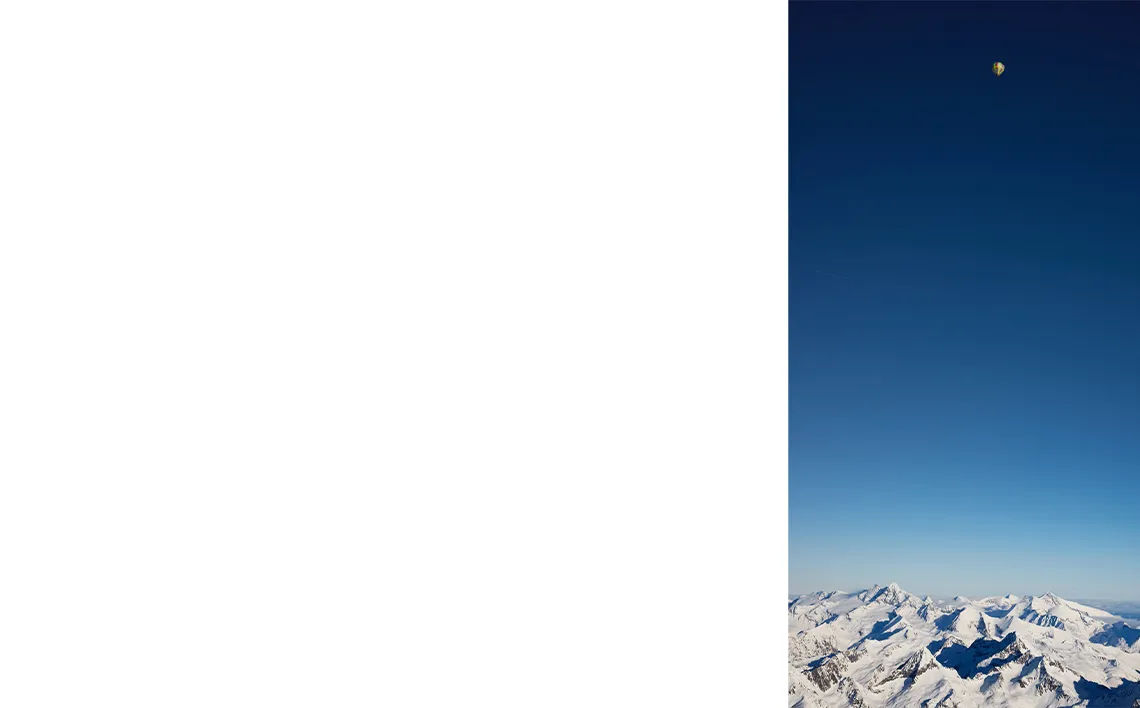

Soon we’ll be flying over the Großglockner, Austria’s highest peak. We must have reached at least 4,000 metres. ‘That’s right’, says Flaggl. ‘But we’re not flying, we’re travelling! Never say flying when you’re ballooning or you’ll be forced to buy a round of schnapps.’

The mighty mountain comes closer. Viewed from above, it looks like a jagged ring with a wide, snowy apron. White chiselled slopes. Barren and cold. A frozen beauty. The view couldn’t be more staggering. Germany to the far north, Austria all around us, Switzerland to the west and Italy, Slovenia to the south.

There’s absolutely no sound up here. A soft wind strokes the gondola briefly but otherwise, the air seems to stand still. Nothing moves. Since we’re moving with the current, there’s no airflow, no headwind. Sailing unimpeded with the tides of the troposphere, we’re a part of the atmospheric flow.

There’s no question: this is the highest-ranking observation deck in the world. There’s no cockpit, no pane of glass between us and the elements. Traipsing through the sky at 100 kilometres an hour, you could easily read a newspaper with no trouble at all.

Soon we’ll be flying over the Großglockner, Austria’s highest peak. We must have reached at least 4,000 metres. ‘That’s right’, says Flaggl. ‘But we’re not flying, we’re travelling! Never say flying when you’re ballooning or you’ll be forced to buy a round of schnapps.’

The mighty mountain comes closer. Viewed from above, it looks like a jagged ring with a wide, snowy apron. White chiselled slopes. Barren and cold. A frozen beauty. The view couldn’t be more staggering. Germany to the far north, Austria all around us, Switzerland to the west and Italy, Slovenia to the south.

There’s absolutely no sound up here. A soft wind strokes the gondola briefly but otherwise, the air seems to stand still. Nothing moves. Since we’re moving with the current, there’s no airflow, no headwind. Sailing unimpeded with the tides of the troposphere, we’re a part of the atmospheric flow.

There’s no question: this is the highest-ranking observation deck in the world. There’s no cockpit, no pane of glass between us and the elements. Traipsing through the sky at 100 kilometres an hour, you could easily read a newspaper with no trouble at all.

Soon we’ll be flying over the Großglockner, Austria’s highest peak. We must have reached at least 4,000 metres. ‘That’s right’, says Flaggl. ‘But we’re not flying, we’re travelling! Never say flying when you’re ballooning or you’ll be forced to buy a round of schnapps.’

The mighty mountain comes closer. Viewed from above, it looks like a jagged ring with a wide, snowy apron. White chiselled slopes. Barren and cold. A frozen beauty. The view couldn’t be more staggering. Germany to the far north, Austria all around us, Switzerland to the west and Italy, Slovenia to the south.

There’s absolutely no sound up here. A soft wind strokes the gondola briefly but otherwise, the air seems to stand still. Nothing moves. Since we’re moving with the current, there’s no airflow, no headwind. Sailing unimpeded with the tides of the troposphere, we’re a part of the atmospheric flow.

There’s no question: this is the highest-ranking observation deck in the world. There’s no cockpit, no pane of glass between us and the elements. Traipsing through the sky at 100 kilometres an hour, you could easily read a newspaper with no trouble at all.

We continue to glide southward, boundless, weightless. Flaggl checks the altimeter and announces, ‘5,521 metres.’ A highly impressive flight altitude – quite literally. Looking south, we spot the Mediterranean for the first time. Passing over the foothills of the Dolomites, we see Cortina d’Ampezzo to the west. To the east lies Monte Zoncolan and toy-village-like Tolmezzo. Ahead of us: Trieste, and down on the right the bays and lagoons of Venice.

It feels like we’re gliding across a map, over the hachure of a gigantic world atlas. Beyond it, a limitless flat surface spreads out like silver paper. The Adriatic, the Mediterranean. The only word that describes it: tremendous.

We’ve been in the air for the best part of four hours, our feet like icicles, when Flaggl begins the descent. He pulls a line, opening the parachute at the top of the balloon, a flap that allows the hot air to gush out. We float gently downward as if in an elevator.

The Italian Plain comes into view. A brown slab, decorated with ever more detail. Flaggl, from the left, ‘2,000 metres and sinking.’ The trickiest part of the journey has arrived. The earth comes closer. Once again, we recognise cars, trucks, streets. And everywhere too: electricity pylons and power lines, which we must avoid at all costs!

The manoeuvre requires skill and a light touch. It’s a bit like trying to force a precision landing from a child’s balloon that’s dancing in the wind. Flaggl: ‘You have to develop a feel for it. Some pilots learn quickly, others never do.’ The veteran balloonist stays calm. He’s done this 7,000 times.

A brown field approaches. The skids touch down. A warm wind wafts over us – we’re in Italy. We’ve landed in a wheat field near the small town of Pordenone.

Climbing wordlessly out of the basket, the passengers can hardly believe their eyes. A farmer is running across the field toward us with two bottles of red wine. The air is warm; birds are twittering and the wine is poured – an unexpected welcome drink in the middle of a field in the middle of Italy. After all, it’s not every day that a big, beautiful hot-air balloon lands right under your nose!

Author

Photographer

Aluminium Collection

Travel companion

Discover the world with us